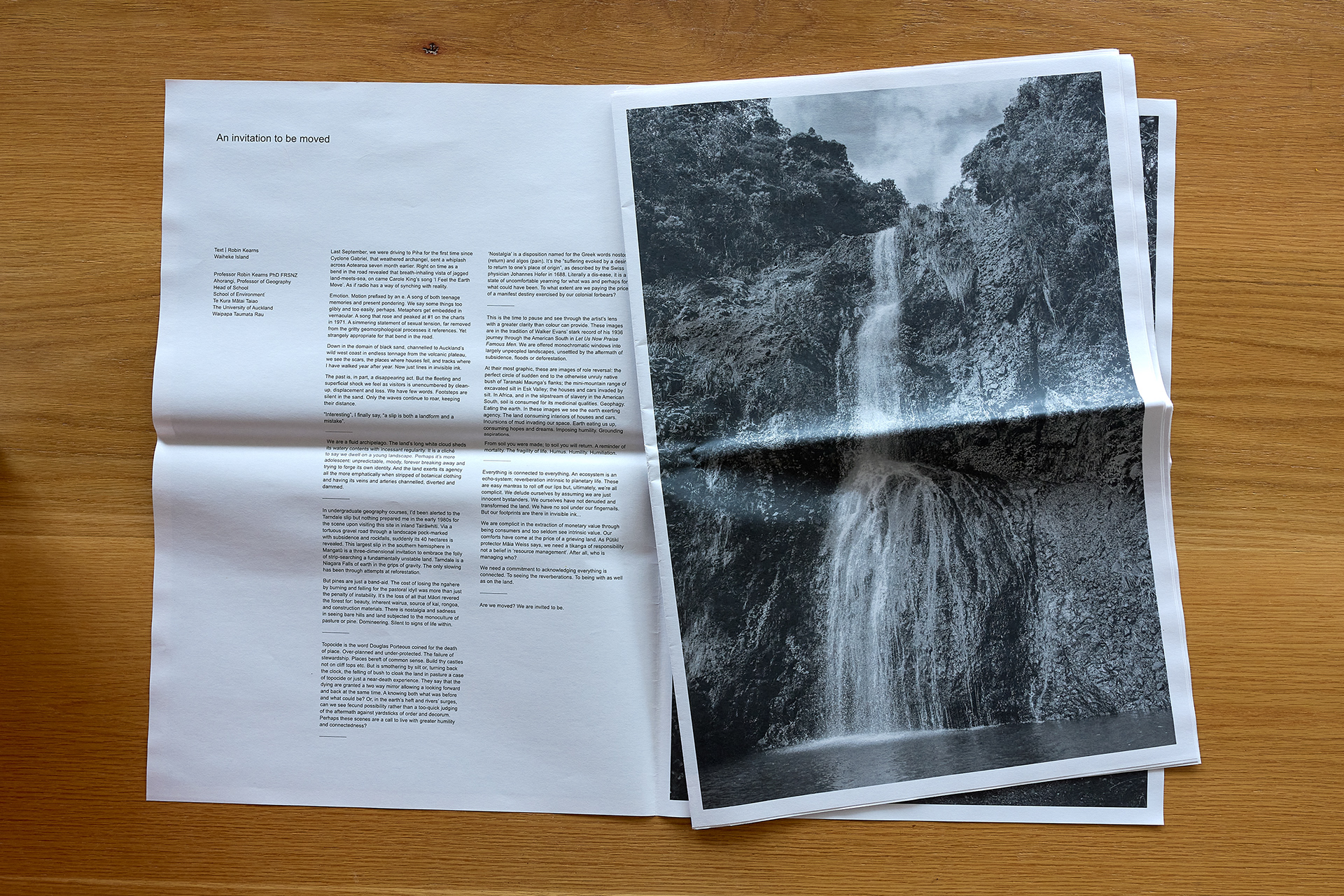

An invitation to be moved

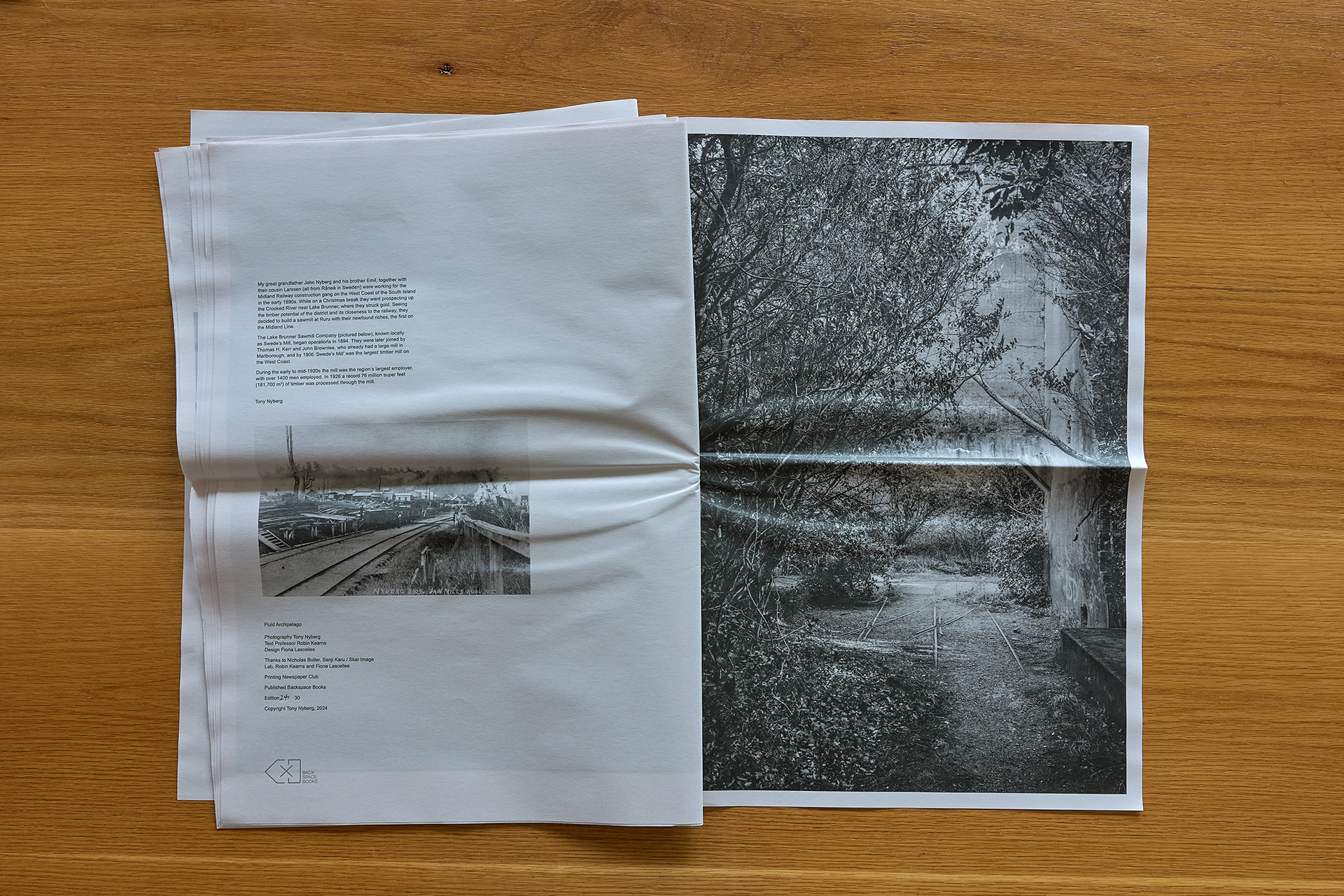

Professor Robin Kearns

Last September, we were driving to Piha for the first time since Cyclone Gabrielle, that weathered archangel, sent a whiplash across Aotearoa seven month earlier. Right on time as a bend in the road revealed that breath-inhaling vista of jagged land-meets-sea, on came Carole King’s song ‘I Feel the Earth Move’. As if radio has a way of synching with reality.

Emotion. Motion prefixed by an e. A song of both teenage memories and present pondering. We say some things too glibly and too easily, perhaps. Metaphors get embedded in vernacular. A song that rose and peaked at #1 on the charts in 1971. A simmering statement of sexual tension, far removed from the gritty geomorphological processes it references. Yet strangely appropriate for that bend in the road.

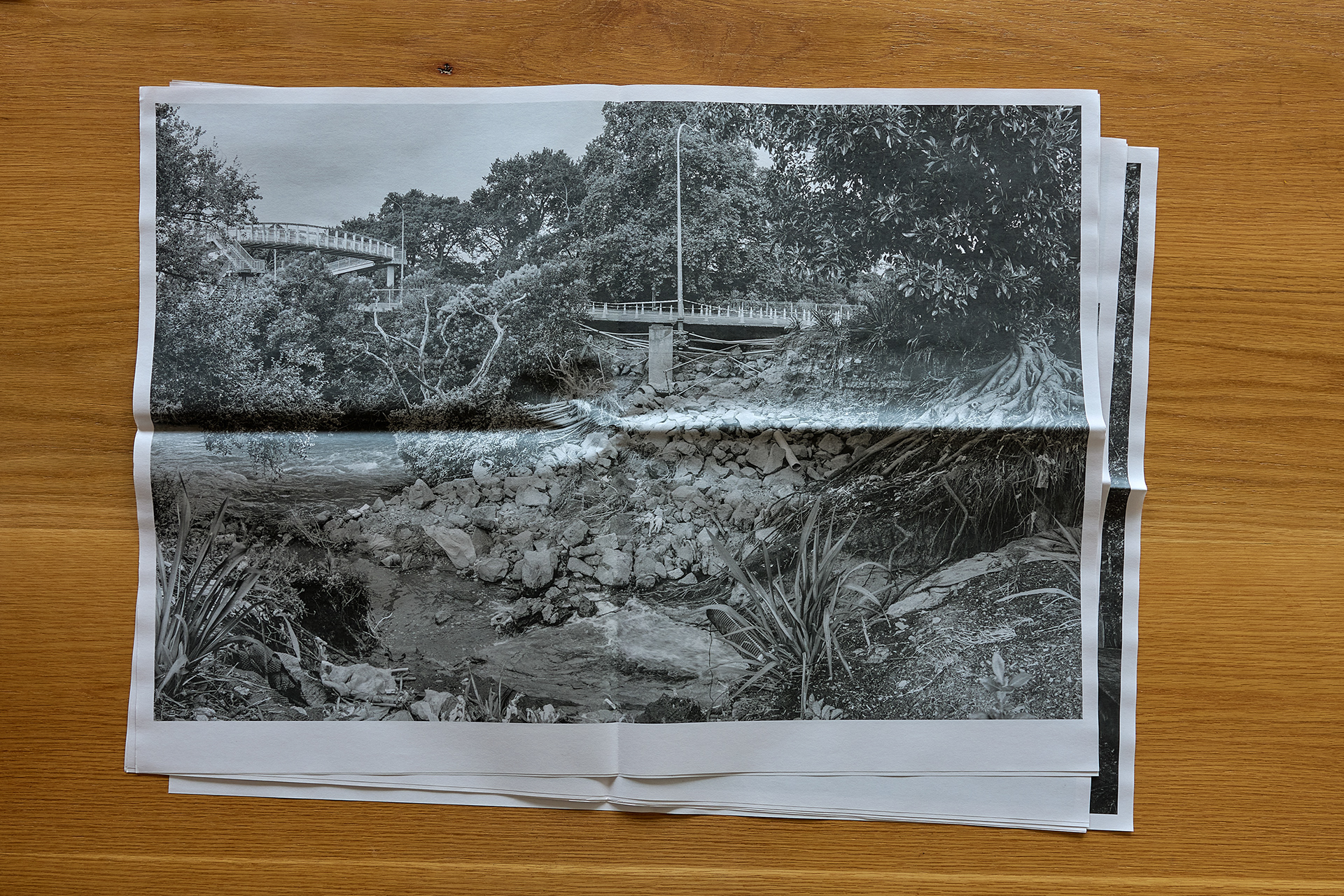

Down in the domain of black sand, channelled to Auckland’s wild west coast in endless tonnage from the volcanic plateau, we see the scars, the places where houses fell, and tracks where I have walked year after year. Now just lines in invisible ink.

The past is, in part, a disappearing act. But the fleeting and superficial shock we feel as visitors is unencumbered by clean-up, displacement and loss. We have few words. Footsteps are silent in the sand. Only the waves continue to roar, keeping their distance.

“Interesting”, I finally say, “a slip is both a landform and a mistake”.

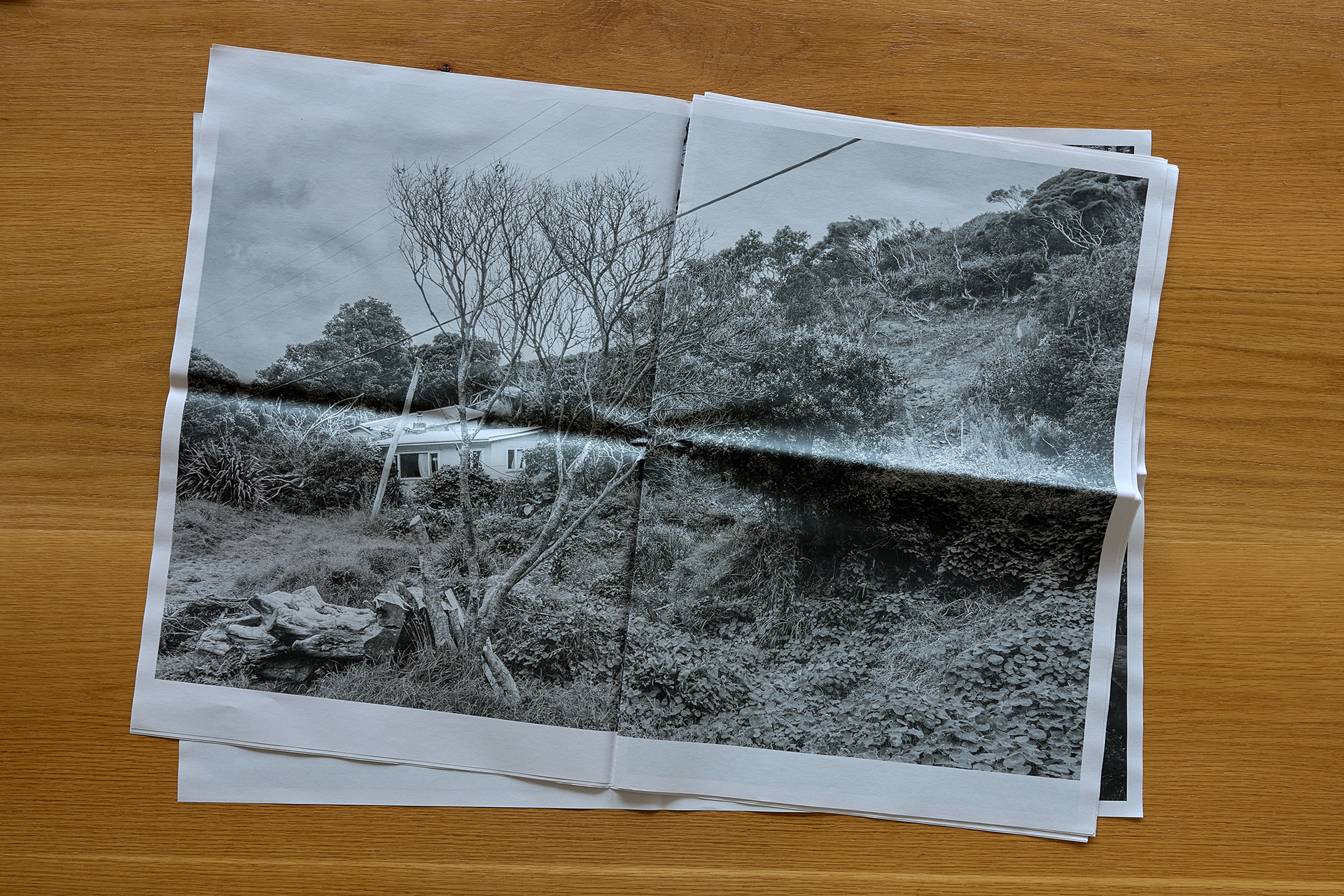

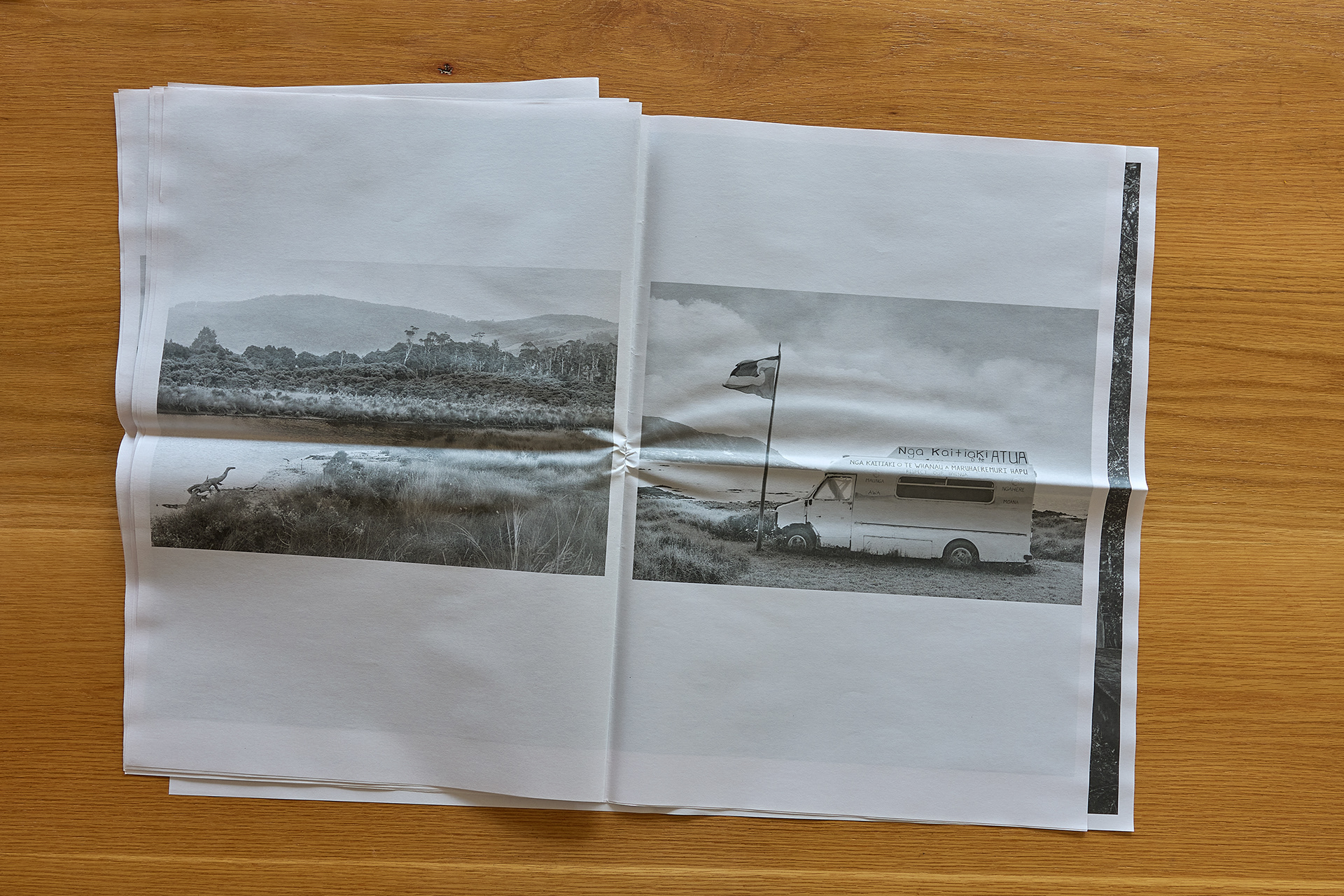

We are a fluid archipelago. The land’s long white cloud sheds its watery contents with incessant regularity. It is a cliché to say we dwell on a young landscape. Perhaps it’s more adolescent: unpredictable, moody, forever breaking away and trying to forge its own identity. And the land exerts its agency all the more emphatically when stripped of botanical clothing and having its veins and arteries channelled, diverted and dammed.

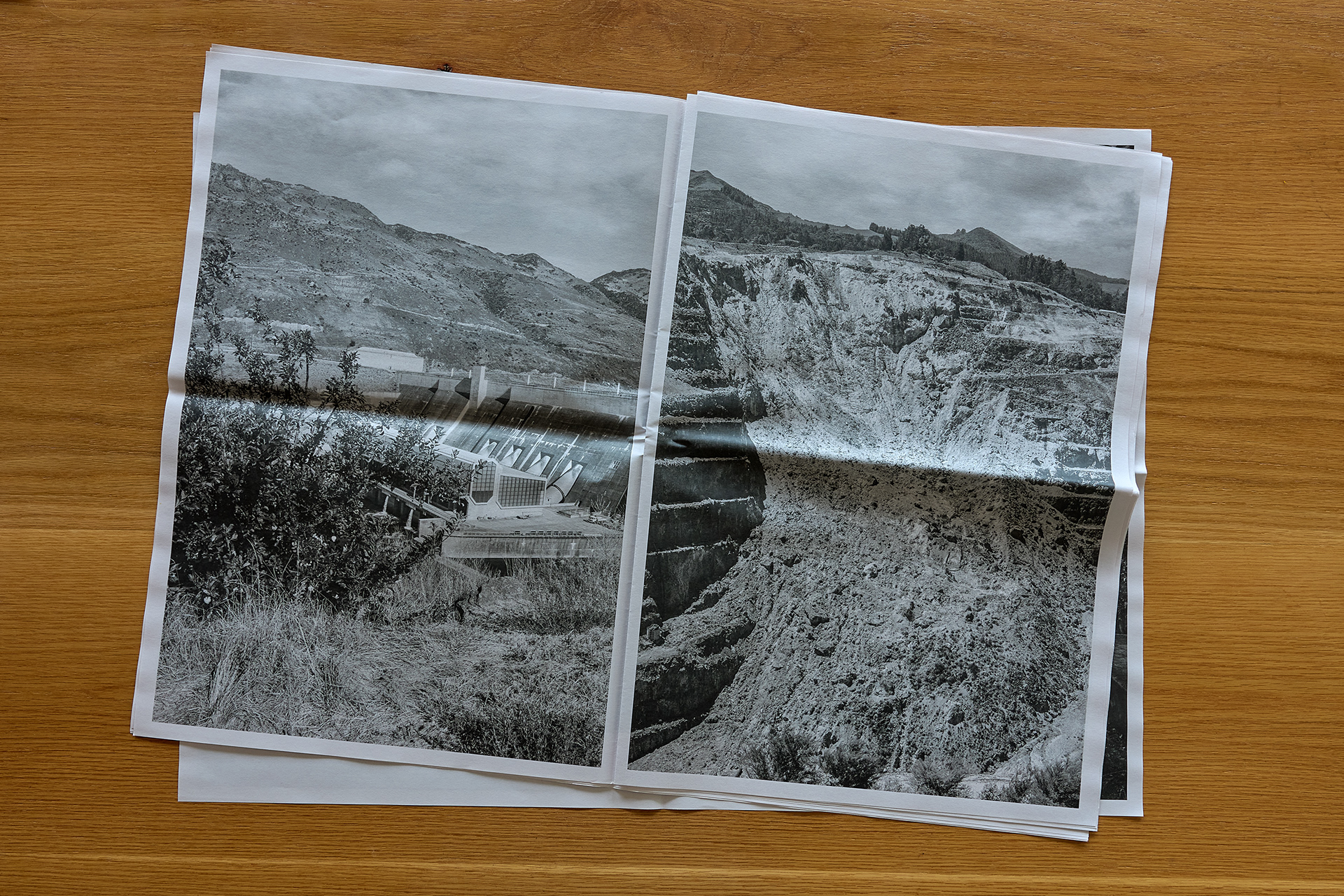

In undergraduate geography courses, I’d been alerted to the Tarndale slip but nothing prepared me in the early 1980s for the scene upon visiting this site in inland Tairāwhiti. Via a tortuous gravel road through a landscape pock-marked with subsidence and rockfalls, suddenly its 40 hectares is revealed. This largest slip in the southern hemisphere in Mangatū is a three-dimensional invitation to embrace the folly of strip-searching a fundamentally unstable land. Tarndale is a Niagara Falls of earth in the grips of gravity. The only slowing has been through attempts at reforestation.

But pines are just a band-aid. The cost of losing the ngahere by burning and felling for the pastoral idyll was more than just the penalty of instability. It’s the loss of all that Māori revered the forest for: beauty, inherent wairua, source of kai, rongoa, and construction materials. There is nostalgia and sadness in seeing bare hills and land subjected to the monoculture of pasture or pine. Domineering. Silent to signs of life within.

Topocide is the word Douglas Porteous coined for the death of place. Over-planned and under-protected. The failure of stewardship. Places bereft of common sense. Build thy castles not on cliff tops etc. But is smothering by silt or, turning back the clock, the felling of bush to cloak the land in pasture a case of topocide or just a near-death experience. They say that the dying are granted a two way mirror allowing a looking forward and back at the same time. A knowing both what was before and what could be? Or, in the earth’s heft and rivers’ surges, can we see fecund possibility rather than a too-quick judging of the aftermath against yardsticks of order and decorum. Perhaps these scenes are a call to live with greater humility and connectedness?

‘Nostalgia’ is a disposition named for the Greek words nostos (return) and algos (pain). It’s the “suffering evoked by a desire to return to one’s place of origin”, as described by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer in 1688. Literally a dis-ease, it is a state of uncomfortable yearning for what was and perhaps for what could have been. To what extent are we paying the price of a manifest destiny exercised by our colonial forbears?

This is the time to pause and see through the artist’s lens with a greater clarity than colour can provide. These images are in the tradition of Walker Evans’ stark record of his 1936 journey through the American South in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. We are offered monochromatic windows into largely unpeopled landscapes, unsettled by the aftermath of subsidence, floods or deforestation.

At their most graphic, these are images of role reversal: the perfect circle of sudden end to the otherwise unruly native bush of Taranaki Maunga’s flanks; the mini-mountain range of excavated silt in Esk Valley; the houses and cars invaded by silt. In Africa, and in the slipstream of slavery in the American South, soil is consumed for its medicinal qualities. Geophagy. Eating the earth. In these images we see the earth exerting agency. The land consuming interiors of houses and cars. Incursions of mud invading our space. Earth eating us up, consuming hopes and dreams. Imposing humility. Grounding aspirations.

From soil you were made; to soil you will return. A reminder of mortality. The fragility of life. Humus. Humility. Humiliation.

Everything is connected to everything. An ecosystem is an echo-system; reverberation intrinsic to planetary life. These are easy mantras to roll off our lips but, ultimately, we’re all complicit. We delude ourselves by assuming we are just innocent bystanders. We ourselves have not denuded and transformed the land. We have no soil under our fingernails. But our footprints are there in invisible ink...

We are complicit in the extraction of monetary value through being consumers and too seldom see intrinsic value. Our comforts have come at the price of a grieving land. As Pūtiki protector Māia Weiss says, we need a tikanga of responsibility not a belief in ‘resource management’. After all, who is managing who?

We need a commitment to acknowledging everything is connected. To seeing the reverberations. To being with as well as on the land.

Are we moved? We are invited to be.